Optimizing brand architecture for healthcare systems

Businesses of growing healthcare systems could be damaged if their portfolios are not harmonized

The landscape of healthcare providers continues to evolve as we see continued, albeit slowed, consolidation. Many of the larger networks are benefiting from increased financial discipline, improving operational margins from acquisition synergies, and the gradual shift from a pay-for-service model reliant on capital intensive facilities to lower cost, market-relevant channels of delivery. The result of this industry transformation is fewer, larger enterprises with expanding services.

With prospects for growth, sustainability, and market power come the potential for negative effects of increasing complexity. Healthcare systems are becoming some of today’s most complicated business organizations, challenging efforts toward simplification and integration so critical in the consumer experience.

As networks grow, multiple ownership models, varied organizational relationships, and increased service offerings result, heightening the potential for a fragmented identity and incohesive portfolio. Without a concerted plan to harmonize how entities across the enterprise are expressed, healthcare systems run the risk of confusing stakeholders, sub-optimizing investments, fracturing culture, and causing unnecessary stress among those tasked with managing brands.

Learn More: 3 Ways brand and marketing can create more human health care experiences

While a plan to harmonize entities, referred to here as “brand architecture”, can help to mitigate these risks, there are a variety of approaches and perspectives to consider in addressing the idiosyncrasies of each system. This article compares different approaches to brand architecture, specifically for healthcare systems, and how leaders might determine the right one for their organization based on a set of factors most critical in decision making.

What is brand architecture in the context of healthcare systems?

The term “brand architecture” has been used since it was originally coined twenty years ago by David Aaker in his seminal article titled: The Brand Relationship Spectrum: The Key to the Brand Architecture Challenge. Since then it has been an invaluable tool corporations use to conceive and coordinate identities of various entities within their portfolio. Brand architecture is defined as the organizing structure of the brand portfolio that specifies roles and relationships between brands. Expanding on this definition, brand architecture might include the relationship of all entities, not only those that are brands, to their corporate parent and to each other, as well as specific offers that come from those entities.

Key terms that came out of early work are still in use today including “branded house”, “house of brands”, and “endorsed brands”, which act as effective referent points for considering different approaches. While helpful in framing options for determining relationships of identities, the realities for most organizations is that they have different types of brands they manage. In certain instances, they have a clean branded house, and in others they maintain sub-brands, endorsed brands and even stand-alone brands identified with a house of brands schema. While an overriding approach helps to anchor the portfolio and present “the argument to beat” for a given business, an “either/or”, rigid approach many strategists recommend just isn’t pragmatic or responsive to real and dynamic situations of the market.

This is especially true in healthcare, where we might define brand architecture as the approach toward organizing the identities of entities including physical facilities (e.g. hospitals, convenience care / retail facilities), service lines or centers of excellence (e.g. oncology, cardiology), and organizations (e.g. medical groups, foundations) in relation to a parent company. While these decisions might be obvious for the top, often compared, systems with unquestionably powerful brands such as Mayo Clinic and Cleveland Clinic, most networks do not have near their brand equity. Even the largest multi-regional players must take a more nuanced approach given their situation and aspirations. This becomes important as these businesses grow through mergers and acquisitions and must weigh the true power of their brands against those of partners in new markets and/or service areas. Moreover, there are political issues to consider as well as an anti-corporate sentiment potentially growing in the healthcare market as skepticism grows when large players get even larger.

Learn More: 3 Strategies for building consumer trust, and what to do if you’ve lost it

Pros and cons of the best approaches being utilized today

Most healthcare systems recognize the great potential in a masterbrand to reinforce the market desire for “system-ness”, continuity, and simplicity, so we have seen an increasing number of providers moving toward a “house of brands” strategy. Even one of the largest systems in the country, Ascension, who had allowed its 67 acute-care hospitals and medical centers in twenty states to operate somewhat independently with distinct identities, is now intensifying efforts to integrate and present a more unified identity by moving toward a masterbrand strategy where entities carry the Ascension name and logo.

While simplifying identities and leveraging a parent brand across a healthcare enterprise makes sense, the degrees of parent dominance can vary greatly. So, what are the distinct approaches within a masterbrand spectrum? While there are shades of gray, these four approaches represent the most distinct types, ranging from most to least parent dominant.

Isolated Masterbrand

The most dominant parent brand configuration allows no other facility, service, or organizational name to be added to it, thus separating it and therefore presenting the simplest identity possible to the public. This approach, which goes beyond dominance, might be called an “isolated masterbrand”. It leaves no question as to which brand is leading every interaction in the stakeholder experience, or which brand is the authority in every instance. This approach is the most workable and elegant when it comes to identifying the variety of entities with long names inherent in healthcare. Examples of this approach include Novant Health, MercyOne, and Northwestern Medicine.

As we investigate brand architectures of these systems, we see the names of entities such as major hospitals or service lines being consistently expressed but not overtly connected to the master brand name or logo – some separation or remoteness is maintained, allowing the master brand to stand on its own. While this approach is the cleanest, most confident expression of a system, and can effectively simplify things for consumers, it carries challenges in balancing strong equities of entities with established reputations and runs the risk of being interpreted as overly corporate, and rigidly homogenous.

Dominant Masterbrand

The second most dominant parent brand configuration allows for limited entities to be combined in a clearly subordinate relationship. This approach might simply be called a “dominant masterbrand”. Like the isolated approach, it conveys unity and the leadership position of the parent brand, while allowing for flexibility to include names of entities with strong historic equity or those with strategic importance. Examples of this approach include New York Presbyterian, Mount Sinai, and Advent Health.

Upon investigation of these brand architectures, we see treatments of logos and names which always position the parent brand first and boldly, and the entity name second in a consistent arrangement or lock-up with the parent name. One of the benefits of this approach is that it sets up the potential for a “brand equity loop” from the parent brand to the connected entity and from the entity back to the parent if it has equity such as a single hospital or service line with strong reputation. The parent brand in this approach can be diluted, however, if this configuration is overused and applied to minor services or programs vs. using strict criteria and allowing limited types of entities to hold a support position to the parent.

Learn More: What today’s health care marketers need to know about Gen Z

Shared Masterbrand

The third most dominant parent brand configuration allows entities to be combined with the parent brand in an almost equal weighting, or what might be called a “shared masterbrand”. While this approach always positions the parent brand in the lead position, the emphasis of the entity name is a very close second. Examples of this approach include Hackensack Meridian Health, Banner Health, and in Ascension Health’s new masterbrand strategy.

While this approach can reduce perceptions of corporate dominance, it can result in long, unwieldy names and confusion over which brand or entity is leading vs. supporting, and therefore can be overwhelming for consumers. It can fight the natural tendency of consumers to truncate names to the shortest, most efficient expression of the brand. If names get too long, acronyms or “alphabet soup” initialisms will emerge that might not be in the company’s best interest.

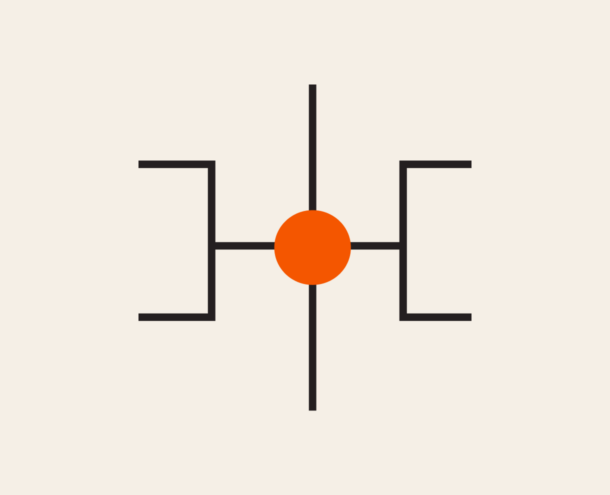

The least dominant parent brand configuration allows for much more flexibility in its relationship with given entities. At times, it’s in the lead or first position, and at other times it’s in a strong support or second position depending on the type of entity. While the parent brand’s position can change, it is clear and obvious, through a consistent visual identity, that the entity is an integral part of the network. This approach might be called a “flexible masterbrand”, as it is part dominant, and part endorser, and is a good example that purity in brand architecture is not always the best solution for a complex system. Examples of this approach include Northwell Health and Atlantic Health.

While flexible, it should be noted that the best use of this strategy still applies a systematic approach to when and where the masterbrand is in lead vs. support position. For example, many systems allow major hospitals or medical centers to hold lead position, but any enterprise-wide service line begins with the masterbrand followed up by the service line name in support position (as illustrated above).

This approach can be very pragmatic while building the masterbrand (albeit less efficiently), but it runs the risk of being cumbersome and confusing to consumers, as the role and position of the masterbrand switches depending on entity type – a sound strategy that might come off as a compromise lost on the public. Furthermore, this approach, like the shared masterbrand, makes it easy for the market to default to the secondary, more familiar, name (typically a hospital which has been acquired), and thus prolongs a transition toward the masterbrand and accrual of its equity.

Reach out to us with any questions, or to continue the conversation.