Part 2: Optimizing Brand Architecture for Healthcare Systems: One-size does not fit all

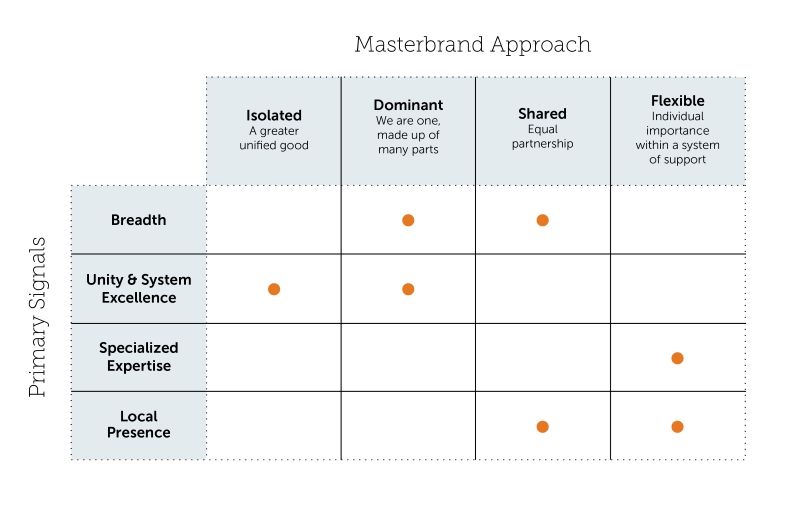

What each approach signals to audiences

In addition to the functional aspects of these approaches, it is also important to consider the very different messages each one sends to internal and external audiences, as well as the expectations that follow. From a brand portfolio perspective, there are four, essential, things large providers need to communicate to be relevant and credible in today’s healthcare market, including:

Breadth – expansiveness of the network

Unity & System Excellence – togetherness of the network

Specialized Expertise – established excellence in strategically important areas

Local presence – ties to individual communities

While these messages can be delivered broadly in marketing communications, the dominance of a parent brand has a direct relation to what the enterprise is signaling to employees and the market, and therefore how it conveys these four.

In an isolated masterbrand strategy, the priority among these is to convey unity and corporate authority. This approach signals extreme homogeneity in a singular identity across the enterprise by consistently expressing the masterbrand in an un-obstructed, unfettered, and uncompromised way.

For employees, this signals a “greater unified good” message that diminishes tribalism that can result from maintaining individual identities of hospitals or other entities. It sets up the expectation that enterprise protocols are well established and should be followed, and that all entities and employees are equal.

For external audiences, this signals a certain confidence, system excellence, and power that can only come from a single source. Like the strongest consumer brands, it sets up the expectation that every experience will be consistent and reliable with no variability in service at different facilities. When executed well, an isolated masterbrand strategy most effectively expedites a halo effect that benefits the enterprise and all the entities within the organization.

Breadth of the network is expressed in systematic, unilateral ways with very few exceptions. Because of this, it can be difficult to emphasize local presence in the brand architecture, without bending the rules of this austere strategy.

Learn More: 3 ways brand marketing can address health care’s cost problem

Dominant masterbrand strategy

In a dominant masterbrand strategy, a combination of unity and breadth of the system is conveyed by allowing prominence of entities such as hospitals and service lines in a support position to the parent brand. This approach says to the market that the parent is the clear masterbrand, while honoring the legacies and community ties of individual hospitals that might have been acquired over time.

For employees, this signals a “we are one, made up of many parts” message that strives to strike a balance between unilateralism of the corporation and individualism on hospitals and other key entities. While it celebrates pride that employees have in hospitals where they work, it sets the expectation that the network is led centrally and that system-wide operations must be followed.

For external audiences, this signals both a confidence and vastness of the network through the hierarchy of parent brand plus entity name. Like the isolated approach, it sets up the expectation that every experience will be consistent and reliable but with some localization.

While this approach allows for prominence of service lines in the secondary position, it runs the risk of diminishing stand-out areas of expertise by blending them with how other service lines are identified. Therefore, some relaxing of the architecture rules might be required to allow for special treatments of these strategically important entities.

Shared masterbrand strategy

In a shared masterbrand strategy, the priority is to convey breadth of the system while emphasizing local presence. This approach signals an equality between parent and entity more so than any other strategy.

For employees, this signals an “equal partnership” message that maintains considerable presence of hospitals and service lines within a consistent expression and identity. Like the dominant approach, it celebrates pride that employees have in their individual hospitals, while gently setting the expectation of system-wide operations.

For external audiences, this signals a compromise which can work if combined names are short enough, but runs the risk of making it difficult for stakeholders to use and remember. Another risk of this approach is that is comes off as a less confident expression of the masterbrand, and more politically driven than consumer driven.

While not the primary message, if handled well, this approach can lend itself to highlighting areas of expertise because the diminished role of the partner brand as compared to other strategies.

Flexible masterbrand strategy

In a flexible masterbrand strategy, the priority is to convey local presence by allowing community hospitals to take a lead position in the architecture, while attaching the parent brand to select service lines that demonstrate specialized expertise. This approach signals the most heterogeneity of the four, by emphasizing entities over the parent brand in many instances.

For employees, this signals an “individual importance within a system of support” message by allowing hospitals to prominently occupy first position within a common look and feel expression. While system-ness and shared operational procedures are suggested with this approach, it is conveyed in less obvious and dictatorial ways.

For external audiences, this signals the importance of individual entities throughout an integrated and coordinated system. It says that consumers can maintain relationships they have with their local hospital, but know that when they need it, a much broader and more powerful network full of expertise is available to them.

While breadth is certainly conveyed in the aggregate of entities, because the influence of individual hospitals, for example, is highest in this approach, special efforts should be made to express the spectrum of other facilities and service lines. This unity message is the least clear with his approach, as a variety of identity types exist that make for a more complex architecture and increased potential for confusion.

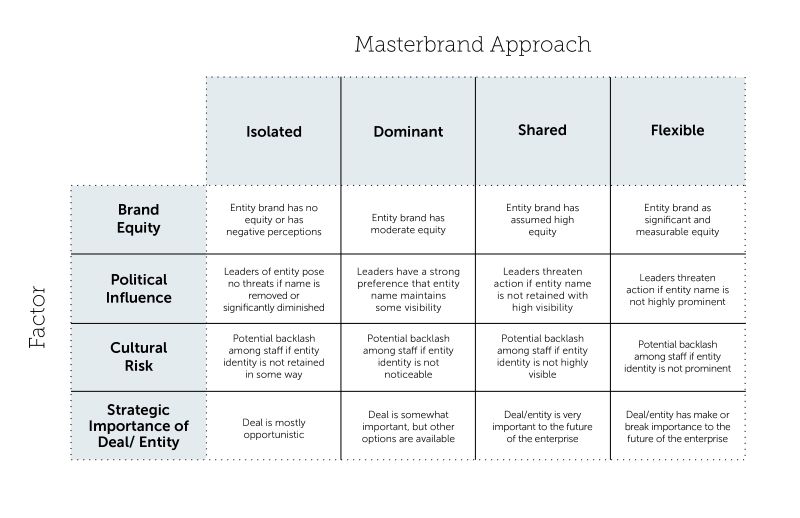

Key factors in determining the optimal approach

As discussed, some degree of masterbrand is most likely the best general strategy for large health systems but determining the right specific approaches can be tricky. The following four factors are the most prevalent I have seen after working with numerous systems in determining the right system-wide or deal-specific approach. For most situations, different factors will vary in relevancy and importance, but this chart frames scenarios as guidance vs. hard and fast rules to consider in determining the best brand architecture answer. If several of these factors are relevant, each one should be weighted before applying to a situation, whether it’s a merger with another large system, acquiring a one-off business, or leveraging an existing hospital or service line. The term “entity” used in the chart below refers to any one of these examples.

Brand Equity

Brand equity, or brand strength, is essentially the ability of a brand to have high influence on stakeholders’ decision making based on perceptions of that brand and its reputation. Influence on decision making in this context means that associations of the brand are so strong that stakeholders prefer it head-and-shoulders above competitive offers, will pay a premium for it, be especially loyal to it, or go out of their way to be served by it (most relevant in healthcare).

Obtaining true brand equity in healthcare is difficult, as is evident by no system, not even Mayo Clinic, ever making it on to well-known brand ranking lists by notable publishers such as Forbes. While the systems with the best reputations might have the kind of brand equity that fits the description above, most do not. Even the best systems don’t have stellar reputations in every aspect of healthcare, so their brand equity in a specific service area should be assessed if another brand or partner is being considered.

Learn More: Meet the health care disruptors coming for your consumers

When using brand equity as a determinant of which masterbrand strategy to use, it is important to include a dose of reality into any assessment. Often leaders of both large systems and smaller entities have an inflated view of their brand’s equity without having the empirical data to prove or disprove that internally biased assumption. If the data doesn’t exist, and there is even some question as to the degree of brand strength, it is always recommended that data is procured and analyzed before heading into masterbrand decision making. While high rigor and detail is preferred, some data is better than nothing, so pragmatic, economical data collection can always be substituted for extensive research that can be costly. Even qualitative insights can provide a pulse on the market and its sentiment on brands.

While brand equity of the parent as compared to a potential acquisition target / partner can illuminate leadership as to the true strength of the brands in discussion, it typically won’t be enough, on its own, to determine the absolute best strategy. This applies to healthcare, where most brands neither have extremely high equity or severely negative reputations. That said, brand equity is a “must-have baseline” to help inform brand architecture discussions. When it is combined with one or more of the other factors, it can provide a snapshot of the brandscape needed to make difficult decision on which

brand architecture approach is best.

Political Influence

Political influence in this context is the will and ability of a prospect company’s leadership to make and receive demands relative to the future use of their brand(s). Oftentimes, having all the empirical brand data in the world means nothing to leaders who have developed an emotional attachment to their brands. The passion that executives have for their brands, warranted or not by the market, can go a long way in derailing negotiations to keep, lose, or extend a brand. In these cases, a measured and rational approach should be taken, supported by market data that provides as much market-based objectivity as possible to make arguments stronger for change. That said, if leadership “digs their heels in”, it is often not worth fighting for what might be a better, pure brand architecture, and compromise workable solutions.

Conversely, the passion among leadership of a parent / acquirer brand can also influence decision making around brand architecture. Even with brand equity data as a baseline, if both sides share equally strong beliefs of the power of their brands, it can be difficult to negotiate toward the best solution. This is where the different approaches outlined above can be very helpful to show the degrees of masterbrand that can be considered, offering options that are so critical in these negotiations. While an equally balanced co-brand approach is never optimal (confuses public as to which brand is in the lead and can result in long, cumbersome names), these different strategies can help executives with brands determined not to be in the driver position, see viable roles their brand can play, and therefore pave the way toward resolution.

Cultural Risk

It can be a tough pill to swallow for employees of organizations whose brand identities are no longer in the lead. All the business, brand, and market rationale in the world that points to a change in role for their brands doesn’t make it any easier. A diminished or eliminated identity carries with it an emotional punch to the pride and connectedness many feel for their institutions. This becomes most prevalent when individual hospitals become part of a larger system. Often those hospitals have built up strong reputations in the communities they serve, and therefore the potential elimination or demotion of their names should be handled with care. Any change like this is almost always, initially, seen as a bad or threatening thing, resulting in organizational backlash. That said, we often find, like the assumed brand equity point made above, that perceptions of dooms day scenarios can be inflated, and that with the proper communication and attention, these issues can be managed.

To soften the blow, while not allowing for too much compromise that could diminish the potential of the future brand, dominant, shared, and flexible masterbrand options can be considered. When organizational pull is so strong, more flexibility will be needed, but caution should be taken to not give in too much to this factor. While it might be easiest, and in some cases necessary, landing on the most flexible approach carries a potentially large price tag when it comes to efficiently building a new masterbrand in the market that needs clarity, certainty, and consistency. Oftentimes, near-term decisions to maintain prominence of a support brand or entity name, are regretted later when confusion results or efforts to build the masterbrand are sub-optimized.

Learn More: Consumer Segmentation: Meet the person behind the patient

Strategic importance of deal or entity

The final and maybe most important factor to consider in brand architecture decision making is just how important the merging system or acquired entity is to the long-term viability and aspirations of the parent’s business. Obviously, the more important and sizable the deal, the more flexibility is required, if any of the other factors discussed are relevant. As deals get larger, and players involved are of similar size and influence, compromise becomes increasingly important, therefore, shared and endorsed approaches are probably most viable. That said, from a pure brand perspective, it is beneficial to push for the more clarity and certainty that exists in the more dominant approaches.

Conversely, for deals that are not at the “make or break” level, influence of a parent brand can be applied to ensure a more dominant approach is adopted. While the benefits of a strong masterbrand should be clear, another positive effect is in these situations. When the strength of the brand is undeniable, the brand architecture approach with any deal becomes obvious and therefore won’t require much diligence and assessment. When these situations occur, decision makers can jump to either the isolated and dominant approach.

Conclusion

Clearly, one size does not fit all situations, and even within one system multiple strategies might be required. While some flexibility and variety of approaches is called for even in the purist strategies, efforts should be made to maintain a common thread architecture throughout the enterprise to promote cohesiveness, professionalism, and order. A rule-based approach that aligns with the business strategy, encompasses all situations and entity types, and allows for purposeful flexibility is the best way to simultaneously build a master brand while staying responsive to market-specific realities.

We would love to hear what you think of this perspective, and where you found it most helpful. Please reach out to us with any questions, or to continue the conversation.